There is a short, insightful lesson on dreams and memory below. If you want to control your brain rather than have it control you, read on. It is a diatribe to consolidate my thoughts, presented for the pleasure of you, and made in kind for us both.

Reality is what we cannot wake up from, and the rest is a series of dreams. For while we all relate to the collective unconscious that is our dreams, so few of us bother to take note about one of the few secular acts of magic, explained only in the most primitive of ways, that is controlling what we do when we sleep. When we are awake, we see with our eyes, though when we dream, we see what we need no eyes to see.

I don’t talk to you as a hippie or as a salesman or any other dead professional. I talk to you as a creator and a producer and an indulger of some of the waking dreams of humanity, namely art. Whatever reason we have our imaginations, I don’t know. But I am practical. I will not, and cannot, get rid of it, and so all I can do is share it with you.

I can’t claim to speak to what a dream is. A scientist may tell you it’s the brain’s “dump” process, where it forgets what needs forgetting and remembers what needs remembering, which the brain helps you do. If you find yourself a victim of the “Tetris effect,” where everything looks like a series of blocks everywhere you go, then you understand some semblance of what I talk about.

I have, in my mind’s ear, at all times a voice which is always thinking and will not be quiet, and this is not unique to me. I have learned to control this voice and cause it to only think productive things, for my life is limited and I request those years to live as long and as soberly as they may, or otherwise I will have wasted this opportunity to make what I can out of my limited presence in this dark and long universe.

And though I don’t use my mind’s eye as often as its ear, it is used extraordinarily often. The visualisations are never clear; they are etheral wisps that are impossible to describe into words, and I do not say this lightly. The imagination sees things as a result of pulses and not as a result of language, and so whatever approximations it makes out of this language is impossible for me to describe. As somebody who makes his reputation out of describing impossible things, you will understand the misery I feel in failing to grasp this universal constant of imagination, and yet we all understand what it is.

And as dreams are an unconscious imagination, where we may control our mind’s eye when awake but not asleep, it is necessary to devote ourselves to understanding what our dreams mean, how to make the most of them, and in what ways we may be a part of them. There is nothing spiritual about this prospect… it is the simple manipulation of one of humanity’s greatest assets — an evolutionary machine designed to be the most efficient sorting device in all of creation. I unambiguously talk about the brain and how it works.

A full talk about how the brain works and how it best learns and how dreams and imagination plays a part into this learning is a topic for the several books I’ve read on the subject. In sum, the brain works the way it does because it evolved to be that way, and whatever quirks that exist, the things we see as faults, are instead assets.

The brain forgets so it may learn more. We sleep to help forget and to help remember, and to save energy for doing so. Our memories work by attaching our feelings to concepts, and this is why we are excellent at remembering scenes but awful at remembering data such as phone numbers and names. The brain never forgets long–term memories, but instead stores it deep inside, waiting for a “hook,” such as meaningful details, a scene you remember, a smell you thought you forgot, and even an old face, to bring it back to life.

The reason we are excellent at remembering things in this manner is because we evolved in environments where we always had to learn new things, because specialisation is for insects and ancient men were expected to be good at everything in order to survive. Recalling things verbatum, such as mathematical formulae, were useless in an era where you needed to know what berries to eat, what dangers to avoid, and whether or not that animal is something to fight or run away from. We had to remember important details and forget what wasn’t important. The brain is very good at this. It’s why we survive.

When we think of intelligence, we think of it in abstract terms. But there is no need to think of it so abstractly when we understand that, simply, memory is intelligence. To understand what works and to memorise that is intelligence. Memorising skills is intelligence. Memorising the hundreds of tiny rules that make up creating excellent writing, excellent art, and excellent poise, is intelligence. The reason it seems so effortless for a great writer to come up with a pithy statement is because they have done it so many times to the point where they memorise the rules for doing so.

A computer scientist being able to diagnose a problem at an instant isn’t due to some innate brilliance. It’s simply because they have, somewhere in their memory, a similar situation, and so only have to pull it out of the depths instead of creating a brand new one. What appears to be instinct is actually memory; and experience is just having enough memory to do consistently right things at consistently right times. What can be learned, in essence, is learned through memory.

Pilots in training are expected to have 1,000 hours in flight before they are competent. But when they are given a flashcard program featuring a series of dials, and are trained to select within two seconds what those dials mean, it trains their memory for the real world. Pilots with only ten hours in flight who memorise these dials through the program perform just as well with the program as pilots with thousands of hours. But this is no substitute for the muscle memory of actually flying a plane; just in interpreting what the plane tells you.

When the brain dreams and uses its imagination, it injects hooks into your memory and hopes that they never leave. I have dreamed about physical exercise and I have dreamed about my schools and I have dreamed about corrupted amalgamations of games I’ve played and media I’ve watched over my life. Our picture of why we dream is wanting at best, so I can’t explain what it all means. But I understand now that my brain thinks it’s important enough to dream about.

Our imaginations are nice enough for this purpose; indeed, memory champions, the guys (and they are mostly guys) who can memorise ten decks of cards, in order, in an hour, use their minds eye exclusively to achieve these feats. They create memory palaces which they visualise themselves walking through, with each card appearing to them as something extraordinarily remarkable and sensual (such as the three of spades being a Tengu brandishing an onyx shield, which I just came up with in a few seconds), and then playing out those scenes in their head when they need to recall information.

The number combination 315 seems absolutely meaningless, until you imagine it as a pregnant woman under a lamppost with a hitman on the other side. In this respect, a number like 315–434–8300 could be interpreted as the pregnant woman discovering the hitman, hiding into the forest, and then getting surrounded by an infinite number of James Bonds. If this is far–fetched to you, then you understand what makes the technique so effective. Easy–to–visualise information, with a ton of sensory hooks (sight, sound, feel, smell, taste, emotion, the whole monty) are deathly easy to remember.

This begs the contradiction of why dreams aren’t so easy to remember. Well, let’s be honest: nobody understand sleep. Until recently we thought that sleep was just a state of unconsciousness, until we understood that the brain was working extraordinarily hard during sleep, through a scientist taping his nephew’s skull to an electrode machine in the dead of night. It goes through cycles, and by the end of each cycle it likes to clean up its mess made by the previous cycle. It’s necessary then, if we want to remember our dreams, to make a conscious effort to remember each one through the use of a dream journal, and through recalling them during the day.

And lucid dreaming, as I will tell you now, is extremely rare though very insightful when it does happen, because being able to live just a little longer while you sleep, being a part of worlds unknown though still safe in bed, is a miracle. Inducing them on purpose is a pasttime of some memory champions, though the methods are still rudimentary and relies on understanding the cycles of sleep and memorising a rough outline of how the graph works in order to best manipulate your chances of getting a dream within REM and Stage 3 sleep.

There are no sure methods. The most reliable ones involve repetition of “tells” that signal whether or not you’re dreaming, such as poking the palm of your hand to see if the finger goes through, closing your eyes and seeing if the light level changes when you open them, wearing a digital watch and seeing if the time changes when you look away and look back, and pinching your nose and seeing if you can breath through it. Performing these during the day will, over time, allow you to perform them while dreaming, and then hopefully you will have some degree of control in your dream at that point.

It is also essential to recall your dreams and keep a dream journal, because the mind learns best through repetition and strong imagery, and writing down your dreams, in as much detail as you possible can, as if every dream was like a very long novel, will force you to remember your dreams and then be familiar with them when a dream does occur.

The problem of how to initially induce a dream is relegated to how much sleep you can get, consistently, each night. Any distraction, such as an LED light (from your alarm clock, routers, and other electronics), natural light (from your windows), noise (like the weather), and uncomfortable environment (such as temperatures and itchiness), causes you to feel necessary sensory noise and distracts from the process of dreaming, and thus from the process of memory and learning. Memory champions are known to walk into competitions wearing industrial earmuffs and sunglasses with tape over them. One French champion wore horse blinders to a match.

You must sleep as much as you can and as consistently as you can, with no distractions. Understand the shape of the sleep cycle chart, to see whether or not it is worth it to go back to sleep, or to take a nap, or to simply wake up and write down your dreams. In doing so you will become more creative, more intelligent, and earn a mastery of your surroundings and your imagination like never before. There is no hocus–pocus to these methods. It is the infantile science of sleep study combined with the maturity of memory study, and together they give us the best approximation for intelligence that we have today.

And though the methods for memorisation are true, as detailed in books like “Moonwalking with Einstein” and “How we Learn” (which aren’t boring at all, and you can take that from me, who doesn’t write boring and doesn’t like boring), I am more concerned about the methods for dreaming, for they are extraordinarily difficult to study and relies on tired–but–tested rituals in an effort to induce dreams. I hope that the research comes back positive, and with certain results.

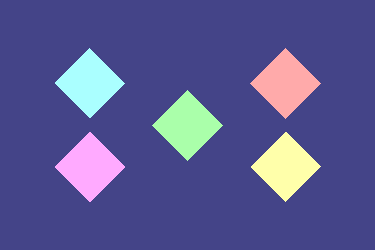

This flag came to me in a pre–sleep vision, where through whatever bizarre combination my brain came up with, envisioned a symbol of autism as four diamonds centered on a flag. I have to thank my brain for that, as it has good taste in vexillology just the same as I do. The symbolism wrote itself, whatever colours I applied to it taking a minimum of effort, and I wrote it down in my sketchbook.

Given a week later where I had spent far too late of time working on this thing, giving it but a day to decide whether or not it was of any quality at all, I came to a few conclusions. The first one was that GIMP is fucking awful for making large flags, where all guides must be applied manually, bitmap shapes aren’t symmetrical, and any geometric construction is a hack at best and rudimentary at worst. The second was that all flags are silly in their own way, and the best we can do is indulge in that silliness, hence what I call the SNES Flag.

But the flag itself gets rid of all the typical symbols of autism, like puzzle pieces and rainbows, because I found them simultaneously patronising and childish and a little bit insulting. Those symbols belong exclusively i elementary schools, and not for the hundreds of thousands of autistic adults who are afraid to talk about their condition because of its childish reputation. This is not helped at all by the unfair use of “autistic” by the same group of people who say transgenderism is a mental illness while jacking off to exploitative intersex porn and calling eachother faggots on 4chan.

I had aimed in full to keep the good of the symbolism and remove all of the bad. There’s an image in my head that haunts me describing “AUTISM” as “Always Unique, Totally Interesting, Sometimes Mysterious,” which is once again patronising. It would be more effective to describe famous people who had autism rather than making a worthless blanket statement, though given the cottage industry of posthumously describing absolutely everybody with Asperger’s, it would be extremely difficult to create any such graph without resorting to unfamiliar names or otherwise libel.

The blue field represents the prevalence of diagnoses in boys, dark blue to avoid any sense of immaturity, though when viewed under certain conditions it may appear as purple, including the minority of female autistics. It is a traditional ratio of 2:3, originally the irregular 7:11 to represent unorthodox ways of thinking traditional of autism, though I dreaded the awkward amount of space that ratio forced.

The five diamonds are each a different colour, and their hex codes are orderly compliments, representing the familiar trait of aspies requiring their work be in ordnung, as reinforced by the geometric symmetry typical of flags, and the diamonds themselves just being skewed squares, meaning that even order can bring novelty.

The shapes also form a contradiction; from one viewpoint, taking the diamonds as a single shape leads to a disorienting slant. From another, they appear as if it all of them broke off from the center, like four squares flying away. And from other viewpoints, it appears as a stylised crosshair, figure, and “A”, or two columns of diamonds flanking a center diamond. The ambiguous nature is intentional, as it encourages the viewer to see the flag from different perspectives, much like how our different brains and worldviews work.

The colours have no special meaning individually, though together they form a more dignified version of the traditional “rainbow” metaphor. The colours, organised by putting cool colours on the left and hot colours on the right, with neutral green in the middle, represent autism being a diverse spectrum, though slotting the colours into more easily defined groups than what a rainbow implies. All the colours compliment each other, showcasing a unity amongst autists, separate as they are, which naturally binds them together.

Now as for whatever other work my dreams come up with, or whatever motiviations it has for imploring me to do this work, I know not. What I do know is that this flag will be little used and long–forgotten, as my obscurity is as obvious as my tendency to talk about the unexpected, such as the above dream diatribe. I can envision it on buttons and being flown, but whether people will fly it is their choice. I would be proud if that were the case, for a people who have been infantilised for so long could do no better than the mature symbolism which I have created out of nothing more than my bare hands, a pipe dream, and good enough intention to showcase it with dignity.

And, for good luck, I have uploaded a source file with the guides I hacked together with the flag.

Date: 2017–03–08. Size: 1,164 bytes. Colours: 6.

Upscaled Dimensions: 750×500. Original Dimensions: 375×250.